Avery Cotton, Reporter

@averyccourant

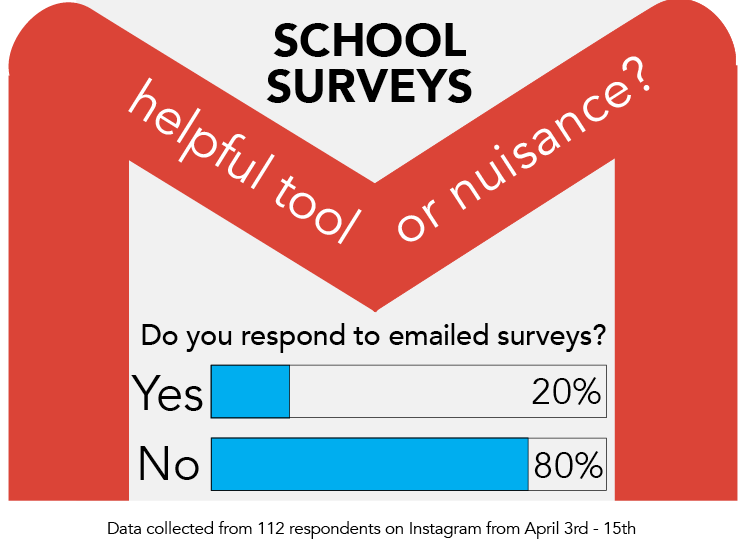

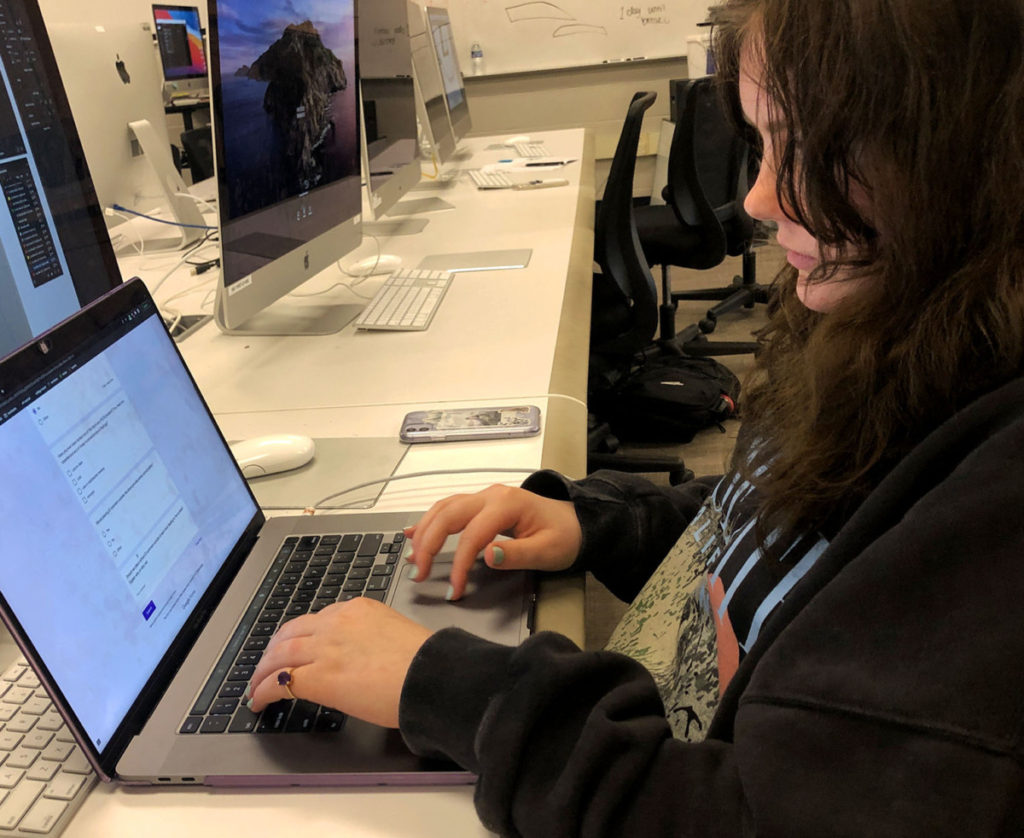

An email notification shatters the silence of a diligent history class, typing away at their laptops for an independent research project. The student clicks on the email, realizing the source of the sound—another school survey. Since they first appeared, school surveys have become a part of the school’s digital culture, with students and staff harboring different opinions about the utility of the surveys.

Some students, like sophomore Trifan Macintire, have doubts about the efficacy of school surveys in enacting change. “Surveys in regards to things within the school, particularly like homework and course load, are more likely to cause change than something on a national scale, like racism, or even on a broader town scale,” Trifan said. “I initially used to take surveys very seriously, expecting that they would cause some change. But as time went on, I realized they weren’t producing much effect.”

In March, a survey about bicycle habits and lanes in New Canaan was circulated to the student body. “I was pleasantly surprised to see that someone else was aware of the shortage of bike lanes in New Canaan,” Trifan, an avid cyclist and proponent for increasing the number of bike lanes in New Canaan, said. “But realistically, I feel like the administration is not going to do anything with the information. There are a few too many surveys going around—a couple surveys per week is fine,” Trifan said.

The origin of the school surveys can be traced to Ari Rothman, assistant principal and the distributor of the school surveys. “A couple years ago, kids started sending surveys to me,” Mr. Rothman said. “The surveys were part of the research that students were doing for assignments in different classes.” Ever since, members of the school community have sent dozens of surveys to Mr. Rothman, the majority of which were conducted by students as part of school research projects.

According to Mr. Rothman, several different classes have held assignments in the past that necessitated the distribution of surveys, one of which can be attributed to an English class performance task project. “This project is intended to develop a plan of action for a real world issue and to present that plan to an appropriate audience,” Mr. Rothman said. “What kids are doing for that assignment is coming up with a specific issue affecting the town, or the school, or student life, and gathering data as they form their arguments.”

An additional type of survey, which was responsible for the frenzy of over a dozen emails in the span of a few days back in December, was for business class as part of a market research project.

Even if students don’t want to receive surveys, they can’t opt out. “I’ve had kids write back to me saying, ‘Please don’t send me surveys, please take me off the list,’ ” Mr. Rothman said. “I can’t take you off the distribution list, because it’s the same list we use for official school business.” However, according to Mr. Rothman, surveys have been sent out solely to staff members in rare cases.

To those who wish to send out surveys, Mr. Rothman has a clear message. “I ask that when a student sends me a survey, they tell me what it’s for,” Mr. Rothman said. “It’s up to the student to look at the survey and decide whether it’s valid or not. What good is your data, and how can you use it?”

While many surveys have been conducted by students, a survey distributed to the student body in February was created by a committee of teachers, one of whom was English teacher Jessica Cullen. “We received 873 responses,” Ms. Cullen said. “The committee analyzed that data to look for some trends.”

The survey, which was conducted through connections class, revealed important information about the general sentiment of the student body towards homework. “It was nice to see that some of the assignments students enjoyed validated the teacher’s efforts,” Ms. Cullen said. “One of the big areas that students felt they needed more support was with reading tasks. Many students felt that taking notes for reading assignments was hard to manage.”

Although the survey received a significant number of responses and shed light on the manner in which students view the manageability of current homework loads, Ms. Cullen doesn’t believe enforcing responses is the right path. “Surveys should be kept optional, because it’s hard to force someone to do something,” Ms. Cullen said. “However, doing this survey during connections was definitely a good move—that time is already built into the day. If surveys are given out going forward, that’s a good time to do them.”

Some, however, have not had such fortune in garnering large numbers of responses on their surveys. “I definitely received fewer responses than I wanted. However, my responses were enough for me to get the results and information I needed,” said junior Ella Mihailoff, who recently conducted a survey about school lunch improvements.

Ella’s assignment, like many other student survey creators, was school-related. “In my AP English class we had to write a letter to someone about something in the community we would like to see changed,” Ella said. “One of the requirements was to conduct our own research and one option was sending a survey out to the NCHS students.”

Though Ella received responses from just 36 people, she believes that these responses represent the whole student body to a fairly high degree. “There were common themes among the 36 respondents that could be applied to a larger population of the school,” Ella said. “I would consider doing a survey because it’s helpful for gathering information.”