Luke Huang, Features Editor

@lukehcourant

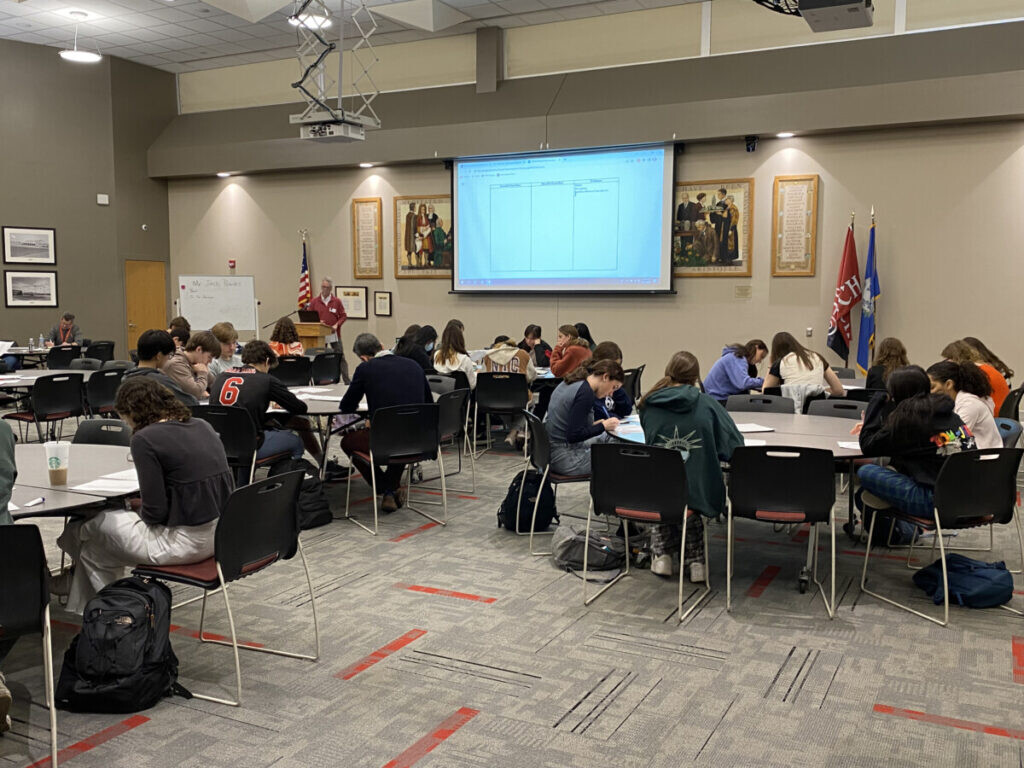

Nestled within the heart of our bustling school, a billowing tapestry of voices forms as the crowd settles in the Wagner Room. To my left, a group of students peruses the program booklet, their voices joining the fluttering of whispers and hushed conversations as they see familiar names. To my right, one student furrows their brow, frantically marking the pamphlet as they seek the perfect word in their last-minute revisions.

A simple microphone awaits on the stage. It stands tall, its silhouette poised to capture the essence of voices to be heard in some moment of transcendence. Behind it, a large projector screen has transformed into a blank canvas, casting a gentle glow upon the expectant faces that fill the room.

But in some vast field of cultivation, where fertile whispers carry the essence of seeds sown and stories untold, a memory amidst some hidden village is unearthed in my mind:

To be a mathematician who sows

contentment in rugged ground,

grows order, precise and fair,

During my freshman year, when the world stood still and isolation seemed impenetrable, the pandemic’s shadow began to recede. It was then that the poem “Fallow” took shape, an embodiment of my admiration for both mathematics and language. As I reflect on that time, I recall struggling to articulate the essence of my poem when my English teacher inquired about its meaning. Trying to confine its meaning within the boundaries of words somehow felt restrictive. But if I, as the creator, couldn’t fully explain it, how could I expect others to grasp its significance?

Within our English classes, poetry often undergoes dissection, with its poetic devices and themes subjected to scrutiny in search of definitive meaning. However, as I contemplate the nature of poetry education, I find myself questioning the effectiveness of this approach. How can poetry be effectively taught? What truly lies at the core of poetry education, shaping our understanding and appreciation of this art form? Standing amidst a crowd of students and teachers, their anticipation palpable, I realize that this gathering is a great place to start.

Poetry in the Classroom

As students first encounter poetry, they often harbor misconceptions, likely vestigial remnants of elementary school days when rhymes and concrete poems adorned colorful picture books.

“It’s not uncommon to believe that poems have to rhyme. They can but don’t have to,” says English teacher Robert Darken. “It’s a double-edged sword with rhyming. It can make students trap themselves into writing forced, contrived, trite things because of the necessity of the rhyme.”

But as most students shed themselves of these easier misconceptions, other ones come along. Many people just aren’t comfortable sharing their personal experiences, leading them to camouflage their experiences with a tangle of literary techniques. Moreover, there’s a common impression that poetry is meant to be erudite, to be just as bewildering as beautiful.

Sophomore Tahlia Scherer is an accomplished writer. During her freshman year, she won a silver key in poetry and earned a national gold medal for a personal essay from the Scholastic Arts and Writing Awards, showcasing her exceptional skills.

Tahlia remembers how during freshman year, she found that because it was hard to write about authentic personal experiences, it ended up hindering the effectiveness of her work. “It’s definitely hard for students to write really well when they feel limitations of how much they should share or not personal.”

That being said, the efforts of English teachers can make a huge difference. “My teacher this year, Mr. Chesbro, always tells us he’ll be our only reader and makes it a safe environment where I feel like I can write my best emotionally driven writing,” she said.

Of course, even though this sort of trust can’t be replicated with some educational model, perhaps there are ways of encouraging creativity. One idea that comes to mind is Poetry 180, a program created by poet laureate Billy Collins, which is meant to build an appreciation for poetry by reading a poem aloud every day.

But in a world where certainty is valued, such activities meant with unmeasurable benefits are a hard sell. As Mr. Darken points out, “New Canaan is good at making data-driven decisions. But reading a poem aloud every day is something you can’t easily link outcomes with.”

Combined with the fact that education focuses more on literary comprehension in general, poetry often ends up being taught in terms of its concepts and techniques. But what does this mean for students?

A Careful Balancing Act

Poetry, like any creative pursuit, is an art that requires balance, where sacrifices and tradeoffs shape its very essence. Nowhere is this more evident than in its pedagogy.

The interplay between the complexities of literary analysis and students’ hesitation to share their interpretations adds an extra layer of complexity to the teaching of poetry. Mr. Darken acknowledges this, stating, “I think there’s a perception that kids are already tentative about their powers of interpretation. You don’t want to turn them off to reading by saying, ‘No, that’s not really what’s going on.’ ”

For Tahlia, teaching poetry through a lens of analysis is a mixed bag. “In some respects, it is important to have the teacher sort of tell you the meaning. Without the instruction, I wouldn’t understand what Shakespeare’s sonnets mean,” says Tahlia. “But then with other poems, there’s like a balance.”

Like most things taught, poetry requires a careful balance between generating interest and teaching the associated skills and concepts. “Of course, a text is subjective, and you can get multiple interpretations. But there’s also a realm of what’s valid, and then there are things that are beyond what’s right,” says Mr. Darken. “There does need to be some instruction about what falls within the realm of valid interpretation.”

For many student poets, learning poetry in English class is often about exposure to a wider poetry genre and learning foundational skills.

Sophomore Amy Meng, an avid writer and reader of poetry, always found joy in expressing her thoughts through words. In eighth grade, she was recognized for her talent and awarded a gold key in Poetry from the Scholastic Arts and Writing Awards. This year, she was awarded an honorable mention in Poetry from the Scholastic Arts and Writing Awards as well as the “Best Use of Imagery” award in the poetry fest organized by English teacher Kristen Brown.

Amy believes that analyzing poems has helped her understand poetry as an artful expression. “English class has exposed me to so many different styles of poetry writing that may not all be the most comfortable styles for me but have taught me so much in terms of the versatility of poetry,” said Amy.

While learning the rules and exploring different forms of poetry can be instructive, it can also impose limitations on students’ writing techniques. Tahlia shares her perspective, saying, “Poetry is one of those writing styles that can be freeing, but I think people don’t see that because they are locked into one certain technique we’re learning.”

Paradoxically, learning and adhering to the rules of grammar and syntax lays the groundwork for creative freedom. “Everybody wants to write like E.E. Cummings with no capitalization or punctuation. That’s fine,” explains Mr. Darken. “But if you know how to conform to the rules of grammar and syntax, then you can break that more effectively. You have to know the rules to break them.”

With these considerations in mind, the question arises: Is there a solution or a model that can strike the right balance in teaching poetry?

Overcoming Misconceptions

When Senior Oliver Gray began his poetry elective course this year, he grappled with a familiar hesitation in his writing. “I would write personal and emotional poems,” said Oliver. “But I was reserved and didn’t want to share them, so I was really cryptic with how I wrote.”

Over the years, the emphasis on learning and analyzing the use of literary devices gave Oliver the impression that they were the heart of poetry rather than a vessel for it. “I would get carried away with extended metaphors that were only vaguely explained at the end. To me, it was a great use of literary techniques,” he said. “But to someone reading the poem, it was a complete mystery.”

But as the year progressed, the self-exploratory nature of the course and guidance from his teacher, Michael McAteer, profoundly impacted Oliver’s perspective. Through their conversations, Oliver understood the fundamental concepts of poetry that would shape his approach to writing.

“The most impactful moment was when he spoke to me about the importance of establishing an audience and recognizing that despite the challenges we face in our personal lives, there are others who have undergone similar journeys,” recounted Oliver. “I tried to picture the people I was writing so there’s more relating to them.”

By comprehending the significance of vulnerability and authenticity, Oliver realized that his own experiences could create a space where readers could find echoes of their emotions. “What I struggled with wasn’t exactly the overuse of techniques, but not conceptualizing them well enough or not providing the reader with enough information,” he explained.

As Mr. McAteer aptly put it, poetry is a concept that can’t be taught directly. While one can impart the building blocks, such as techniques, history, and literary analysis, which form its foundation, a complete understanding can only be attained through practice and application.

Going Beyond the Classroom

Over twenty years ago, when Mr. Darken first came to teach, the English department would routinely go to the Dodge Poetry Festival in New Jersey. “It was like going to a concert, where even though you might not know the artist or about the band when you hear some of their music, you become more of a fan,” he recounts. “I was told these people were great poets — contemporary poets — and having been exposed to that, I got interested.”

English instruction within classrooms is just the beginning, with students just one step away from unlocking a world of possibilities. With advice from her English teacher, Evan Remley, Tahlia discovered various outside opportunities, whether it was participating in poetry contests or joining academic programs.

“When my teacher told me about one state contest, I feel like once I learned that one, it just opened up the doors to many other ones,” said Tahlia. Her enthusiasm for exploration led her to participate in academic writing programs during the summer, which introduced her to even more exciting opportunities.

Similarly, Amy Meng credits continued appreciation for great poetry for her “Best Use of Imagery” award in the poetry fest. “It was simply about reading and writing more poetry,” she explained. “Paying attention to the small things around you and finding inspiration from published poets are very helpful ways to improve.

If you’re eager to embark on your poetic journey, Mr. Darken has some advice. “Just start small,” he suggests. “Pick up a poem by a well-known poet like Billy Collins and give it a read. Then move on to another one. You might be surprised to discover that these poets are connected to a network of other talented individuals. Suddenly, they become relatable, everyday people with extraordinary words.”

As Mr. Darken explains, the key lies in taking that initial step, however small it may be, adding “There is always a choice to do something additional — submit to the spectator, be a part of the UConn poetry contest, or join a writing club. But anytime they decide to do that, it represents enough motivation to tip them into action. And if they take action, once you’ve done it, you think, ‘I can do that. That’s for me.’ ”

From Soil to Soul:

With all this being said, it seems the one role that poetry education could play is clear: to encourage students to embrace experimentation and self-discovery.

Already, students have a platform to engage in bold and creative exploration since the English Department hosts various events and writing seminars during the year. With Ms. Brown’s dedicated stewardship of the Poetry Fest for over 15 years, students are offered valuable opportunities to delve into the depths of their hearts and connect their interests with their learning experiences.

“What we’re doing is offering opportunities for kids to explore what’s in their hearts in a real way,” explains Mr. Darken. “That’s what good education does more generally. If students leave school thinking, there were adults today who told me to do things and I did them, that’s bad. They should see that I had an opportunity to connect my interests with this learning experience.”

Part of poetry education should be about deciphering meaning or understanding literary techniques. But it is about cultivating a love for language, fostering empathy and self-expression, and the opportunity for a lifelong appreciation for the power of words. It is about giving students the tools to navigate the vast landscape of poetry and discover their voices within it.

Whenever my mind drifts towards that memory of the Poetry Fest once again, I remember that sense of purpose and excitement in the Wagner Room. And as I took the steps up to the microphone, I am reminded of the words that echoed in my mind as I wrote “Fallow”:

To be a mathematician who sows

contentment in rugged ground,

grows order, precise and fair,

you must develop a feeling

for those winter times, when green has left the leaves,

but there is still math to till.

Poetry education, like tilling the soil, requires patience, resilience, and a willingness to embrace the unseen potential within each student. It is a journey that begins with curiosity, flourishes with guidance, and bears fruit in the hearts and minds of those who dare to embark upon it.

Of course, perhaps all of this analysis is missing a great point. As Mr. McAteer adds, “In a world that demands certainty, poetry asks us to be uncertain.” Perhaps, in essence, that is the crux of it all.