Keira Cooney, Blogs Editor

@keiraccourant

Julie Song, Blogs Editor

@juliescourant

“Sexism is bad and so is racism. I am not a fan of anyone who does any of that, or thinks any of that stuff,” fourth-grader Max Leffers said. Unfortunately, dismantling such institutions in the classroom is easier said than done. Nationwide, female students are disproportionately affected in terms of attention, challenge, and neglect. So, is the New Canaan classroom as progressive as this 9 year-old is?

“For every five girls that love reading, I have five girls that love math,” South School kindergarten teacher Lisa Charkales said. Despite the fact that girls are often more inclined to humanities studies, Ms. Charkales finds that her students enter their schooling without this particular bias. “Right now, it feels like it’s such a level playing field” said Ms. Charkales.

Ms. Charkales even noticed that, at the young age she teaches, that boys are actually more sensitive. “Girls are more receptive if an answer is wrong.” she said. “The boys will be more likely to internalize.”

As students mature and have more worldly experiences relating to their gender, they are found to exhibit more and more clichéd behavior in the classroom. Such ‘normalized’ gender behavior often is reflected in a difference in aspirations. In Ms. Charkales’ classroom, many girls said that they aspire to be famous singers while the boys overwhelmingly said they wanted to be astronauts.

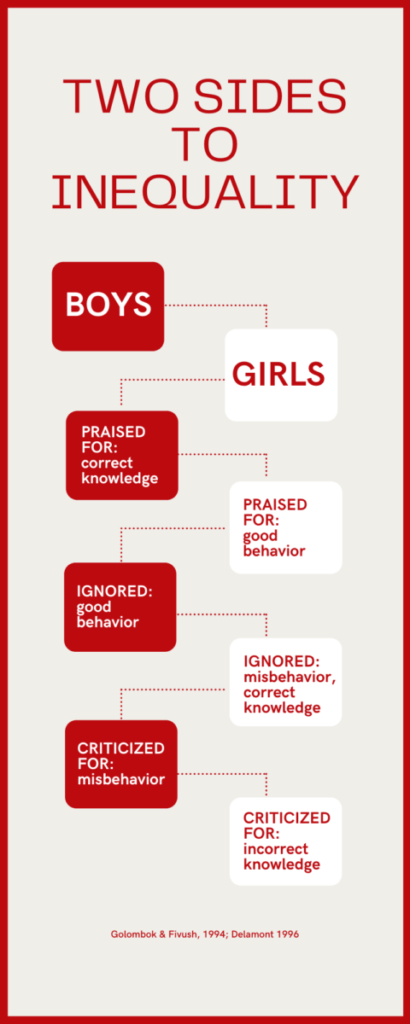

Gradually, the shifts between female and male students’ behaviors become more dramatic, especially in the most developmental years of middle school. In fact, sixth-grade math teacher at Saxe Middle School, Dr. Kristina Paradise, said the largest behavior discrepancy is that girls withdraw, while boys act out. “I see girls as being more inwardly inattentive,” Dr. Paradise said. “The boys, you’re going to give them the challenge problems and things like that because you just need them to sit down and be quiet.”

Unfortunately, for teachers, that difference in classroom behavior makes it all the more difficult to ensure that every student is given the same attention and care. “That makes it harder for girls because they’re not as easily able to be called out for either not understanding, or kind of internalizing that misunderstanding,” Dr. Paradise said.

Female students may be struggling just as much as their male peers during class, but their reluctance to express this misunderstanding, puts girls at an educational disadvantage. While boys are becoming more outwardly expressive as they mature through the schooling system, female students are becoming more submissive in their educational pursuits, a stark contrast from where they began six years ago.

Emotional maturity is an emerging factor that impacts the way the genders interact with each other in class. In middle school, when students have the choice to create groups, they segregate themselves. “A lot of the reluctance to mix gender has to do with the behavior of usually the boys,” said Eighth grade history teacher Andrew Fusci. “Young men use either gender slurs or homophobic slurs,” he said. “It is stand-in for their lack of vocabulary and their lack of really full emotional intelligence. They don’t understand the true ramifications of using those words.”

Mr. Fusci added that this creates a more hostile environment for female students, where they no longer feel safe or comfortable around boys who are not as emotionally mature. Participation and group work become high-stakes social interactions for girls, while boys continue to pursue engagement as an interaction of learning.

As engagement diminishes, so can academic confidence. Girls will often use standardized and tangible evaluations as bases for their intelligence, internalizing bad grades as characterizations of themselves rather than places of improvement. Sixth-grade-student Whitney said, “I feel more pressured in social studies because I never get above an A minus.”

Similarly, one of her classmates, Bea, defined her intelligence by the advanced classes she was taking. Both Whitney and Bea did not consider themselves the smartest in their classes. At this point, middle school girls begin to form opinions about themselves that they carry into higher education.

“The boys in my class, they’re really loud and sometimes, it’s hard to talk loud over them. But… I feel like I say good things.”

Sienna Gutierrez, fourth-grader at East Elementary School

Juniors Eliana Bukai and Avalon Neleman both responded with a resounding “no” when asked if they believed they were smart. Contrastingly, male junior students in the same class, Victor Ralev and Matthew Kim, did. Both boys even agreed that they were some of the top students of their grade as well. Indeed, this confidence is even less prominent in STEM-based classes, where girls lack drive to challenge themselves in these usually male-dominated areas. “I think parents of boys will push them to succeed in the advanced sciences and the harder math classes,” junior Clara Bloom said.

Yet Clara herself, a lover of AP physics and hopeful future engineer, does believe there is equality in education. “I feel like I’ve always been in a positive, supportive learning environment,” she said.

Similarly when asked if the school district has done enough to ensure an equal learning environment for every student, regardless of gender, Mr. Fusci paused. After about a minute of thinking and a heavy sigh, he said, “No.” He quickly added, “I think we’re trying. But, I don’t think we’re quite there.” However, this isn’t to say that the NCPS school district shouldn’t be celebrated for their efforts to work towards an equal learning environment. “I think we have great teachers, I think our central office staff is fully on board with creating an equitable education,” Mr. Fusci said.

Despite the implicit bias in and out of the classroom, there are still students like Clara and Max, who are ambitious and forward-thinking individuals. Younger children are becoming less and less in tune to gender norms, teachers are becoming more supportive of both genders in their individual pursuits, and hopefully, the future will show how great a gender-equitable education can be.

“I say we are approaching goal and we are really close. I know where education was, and I’m really happy with where we’re going,” Mr. Fusci said.