Tahlia Scherer, Features Editor

@tscherercourant

Long gone are the days of number two pencils, the strenuous bubbling in of scantron sheets and the seemingly ceaseless page-flipping of enormous test booklets. All of this, replaced by a singular electronic device and a digital testing system called Bluebook.

Beginning in the fall of 2023, the Preliminary Scholastic Aptitude Test (PSAT), administered by College Board, debuted its first attempt at digital testing. Although College Board claims a majority of the test has remained the same, there are some key differences between the paper and digital versions of the test.

While the core content of the test generally remains the same, the feel, look, and experience appears largely different for students. This fall, junior Spencer Paine took his first-ever PSAT, and his experience differed from his expectations. “I thought it was going to be significantly harder than it was. I don’t know if that was just me, but it seemed like everybody else thought that too,” Spencer said.

For over half a century, the PSAT has served to measure the depth of student knowledge and to give test-takers a glimpse into the real SAT. For many students, the PSAT is their first foray into the standardized test-taking world – one that is filled with months of preparation, dedication and time. At NCHS, the PSAT is not only meant to give students experience, but also to give teachers and administrators insight into the student bodies’ knowledge.

As our society becomes increasingly more reliant on technology, namely with the introduction of ChatGPT, it’s not surprising that standardized testing too, becomes online. As the PSAT shifts to a digital format, College Board maintains that the most important aspects of the test have remained unchanged. Despite this, the College Board website has also said that the test has become “easier to take, more secure, and more relevant.”

But what does this mean for students?

Let’s break it down.

The test comprises two sections called modules, one math and one reading, which are uniformly divided in length. Each module consists of two sections, with the difficulty of the second being dependent on the test-taker’s performance on the first. This adaptive feature of the test provides for a shorter but equally as accurate assessment of student knowledge. These modules measure mostly the same content as the pencil and paper version of the test, and the test is still graded on the same 320 – 1520 point scale.

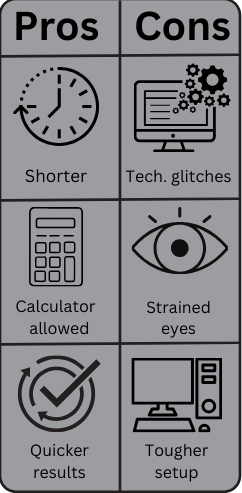

However, some key differences exist: the test is shorter by almost an hour (a little over two hours as compared to the usual three-hour test), each respective question, on average, is allotted more time, the reading passages have been significantly shortened and a built-in calculator is provided for the entirety of the math section.

For administrator Ari Rothman, his experience with the test was different, given that he wasn’t taking the test but rather organizing it. “From the administration standpoint, the Bluebook system that the College Board put together was cumbersome,” Mr. Rothman said. “The system was cumbersome in the way a lot of the essential set up was done – loading students, putting in accommodations, setting up proctoring and room assignments. It simply wasn’t an easy system from the administration standpoint.”

Test coordinator, teacher and English department chair, Evan Remley shared similar sentiments. “The digital format posed some challenges with setting up the admin, having students ready with the browser installed, charged devices, etc. It slowed things down quite a bit at the start,” he said.

When comparing the tests, there is certainly a stark contrast between the digital version and its paper predecessor, at least from the administration standpoint. “The setup, as opposed to the administration of the digital test however, is a lot easier in many ways. The paper version required an enormous amount of physical setup, distribution, and there were always issues regarding the security of the test,” Mr. Rothman said. “The actual set-up of the digital test ended up being a lot easier than having to distribute and then collect all the paper materials.”

However, while the digital version provided for easier set-up, the test itself is now entirely dependent on the proper functionality of technology. “Making sure that the school was in a position to let students take the test was a lot of work. You’re looking at, in this case, 630 kids taking the test, and at a very minimum, we have to make sure the WiFi works,” Mr. Rothman said.

From the student perspective, there were various changes to the feel for the test-taker. “I was expecting the reading section to be longer passages, but instead they felt very short – like one paragraph or maybe even just one sentence. The problems were more focused on one grammatical structure rather than a summary of the purpose of the entire paragraph,” said Spencer. “The math didn’t go up to as high a level of math as I would have guessed too. It felt a lot more condensed and shortened than I would have thought.”

For Spencer, there were numerous aspects of the test he liked and disliked. “ I liked the length, it was manageable within the time frame. I had enough time to go through the test and look back at my work for all the sections. I felt like being able to have enough time to think through what I was doing throughout the whole test made it feel somewhat less stressful,” he said. However, despite this, Spencer expressed he still would have preferred a paper test. “I would’ve preferred to take the test on paper because then I could write stuff down and then flip back,” he said.

Regardless of student and administration opinions, the reality is simple and unavoidable: our world revolves around technology. Thus, a movement toward digital standardized testing is inevitable. “Digital tests are here to stay! They lower the admin costs of these tests by a great deal, and the turnaround on results is far quicker,” Mr. Remley said.

Reflecting on the switch to digital tests and adapting to these changes is imperative to our constantly evolving world. “There’s a lot of research that talks about homework, such as that after two hours of homework a night, the quality just drops off. So, a two-hour test is going to be better than a whole bunch of tests that goes to almost four hours,” Mr. Rothman said. “I think if it’s a streamlined, better test from a student perspective, then that’s obviously going to give us better information on how our programs are preparing kids for these standards.”