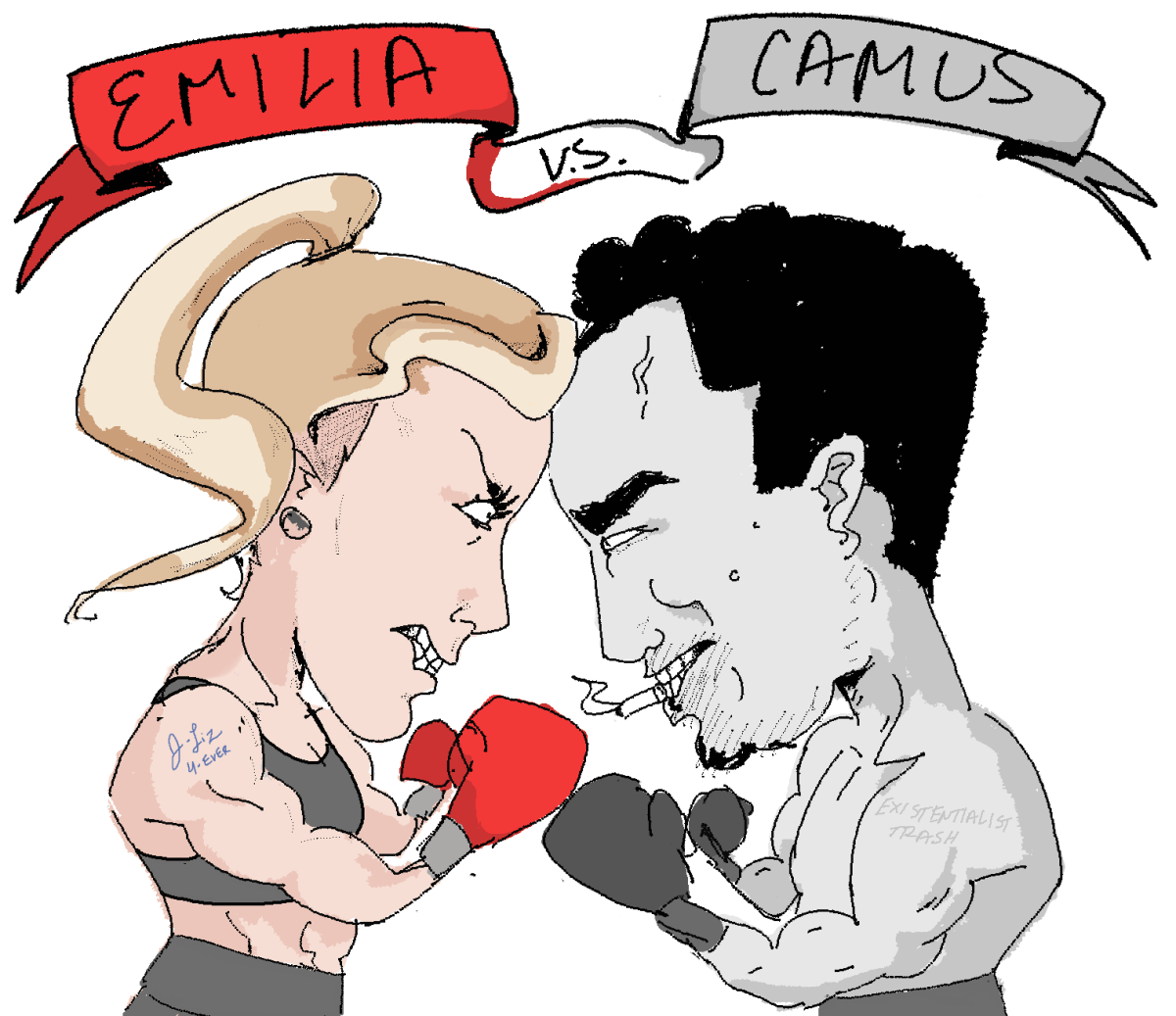

Emilia Savini

Editor-in-chief

@ESaviniCourant

Dear Albert Camus,

While existentialism is certainly not a “light subject”, I was very eager to learn about this challenging philosophical theory. I wanted to learn and to read books that exposed me to groundbreaking ideas about the existence of individuals and how to be a free agent in my life. But sadly, that idealistic approach to the subject of existentialism has been tarnished, and frankly; I blame you, Albert Camus.

My English class was recently introduced to your novel, The Stranger. As I first held that little book in my hands, even the choppy cover art made me shuffle in my seat with pure excitement. However, as I began to read through your work, I became angry. Furious actually. For those of you who are not familiar with this book, here is a super quick summary:

- An emotionally detached man named Meursault lives life purely indifferent to the world.

- He socializes with a sketchy pimp named Raymond and a grungy old man named Salamano who beats his poor dog.

- One day for “no reason”, Meursault shoots an Arab and faces a trial where he ultimately receives a death sentence.

I have never been so angry about the characterization of a fictional character in my life. You created Meursault’s life without any rational meaning or order. None of his life events seem to connect to one another or hold any true sentiment to him. Meursault goes through the motions of being a human, but he does not even deserve that quality. To me, he is a monster. Unwavered by the death of his mother he even complains about having to go to her vigil. It only gets worse when Meursault helps a pimp to lure a woman back to his home just so he can beat her. But still, you insist that there is no reason for these actions. You continue to shove this idea down the throat of the reader, and allow no room for a different point of view.

For myself and the rest of society in this novel, we have trouble accepting this idea of the absurd. To you, the absurd is the idea that people struggle to find meaning and structure in their lives where none exists. Towards the end of the novel when Meursault is put on trial for murdering the Arab, the jury tries to impose meaning on his actions. To me, the jury was being pragmatic; they were looking at Meursault’s life choices and trying to piece together what his motives might have been.

But nope. In your eyes, that is wrong. You deem it unacceptable to impose meaning where he thinks there is none. How could Meursault shoot a person four times for no reason? My mind is boggled by your rationale.

You want us to agree with you; that society was wrong to impose meaning on the stranger’s actions. I cannot do that. Actions are conscious decisions. Meursault did have a reason for his actions. There must be something in the dark caverns of the man’s soul that made him shoot the Arab four times. Whether I can fully comprehend that reasoning, I am not sure. But I am sure that this stranger does have a reason for what he did. This character has a truly twisted mind. His indifference to the world around him is angering, and the very fact that you want me to accept this as “okay” is blasphemous.

I must add that while I deciphered the lines of your work for a deeper meaning, I could not help but be distracted by your word choice at times. I am a strong proponent of unique word choice. However, when you repeat the word “ointment” throughout the book, I cannot help but stop and gag. Reading the word “ointment” makes me instantly imagine an old wrinkly man rubbing lotion on his bunyan-spotted feet. Gross. I tried so hard to understand your philosophy, but throwing in words like “ointment” and “fondle” does not help me stay focused.

Your book has left me beaten and battered. Just trying to understand your message has exhausted my mind and contorted my sense of reason. This is not how I hoped to feel after diving into my very first existentialist text. But on the bright side, now I know what I don’t want out of an existentialist text. Thanks?

Not so sincerely,

Emilia Savini