Julie Song, Editor-in-Chief

@juliescourant

I know that an angel sings when my mom makes doenjang jjigae. When the sultry taste of fermented soybeans hits my senses, I doubt heaven will be much different. My mom’s cooking is delicious. It’s holy, I worship it, I pray for it. It nourishes me like a bible verse and I rely on the fact that even as burnout may singe my brain, the scents of onion and shaved beef in a sheen of marinade or sprouts powdered in red pepper will always peek through the cracks of my door. It soothes me, a reminder that something is waiting, and more importantly, someone downstairs cares. Food can serve as a source of warmth during times of distress. Just as one would pray. Just like one would sing. Just like that, the fearful eat.

And it’s a scary time for an Asian-American. I even wrote a piece a few months ago about the rise in anti-Asian hate. It was a surface-level, expansive work of writing that blanketed a complex issue and tied an optimistic knot. For all the attention it received, I doubt its uninspired message inspired much change.

I’ll prove it to you. Last month was Asian-American and Pacific Islander heritage month. Every morning, the school announcements rang off a clean cut fact about a notable member of the AAPI community. A senator, a poet, an artist, or an athlete maybe, who overcame some hillbilly obstacle from decades ago. The effort is appreciated, but my classmates aren’t ready to hear their names yet. They stuttered through the consonants of these individuals, butchering the syllables and tones of their identity. Snickers, eye rolls, a friend saying “Hey, that’s racist!” through a laugh, unaware that their sentiment is arguably as racist as their counterpart’s indignance. I overheard jokes about AAPI month, so casually scattered around conversations like loose change. I still wonder if these people, my classmates, my peers, my so-called teammates in life, if they’re simply just hungry.

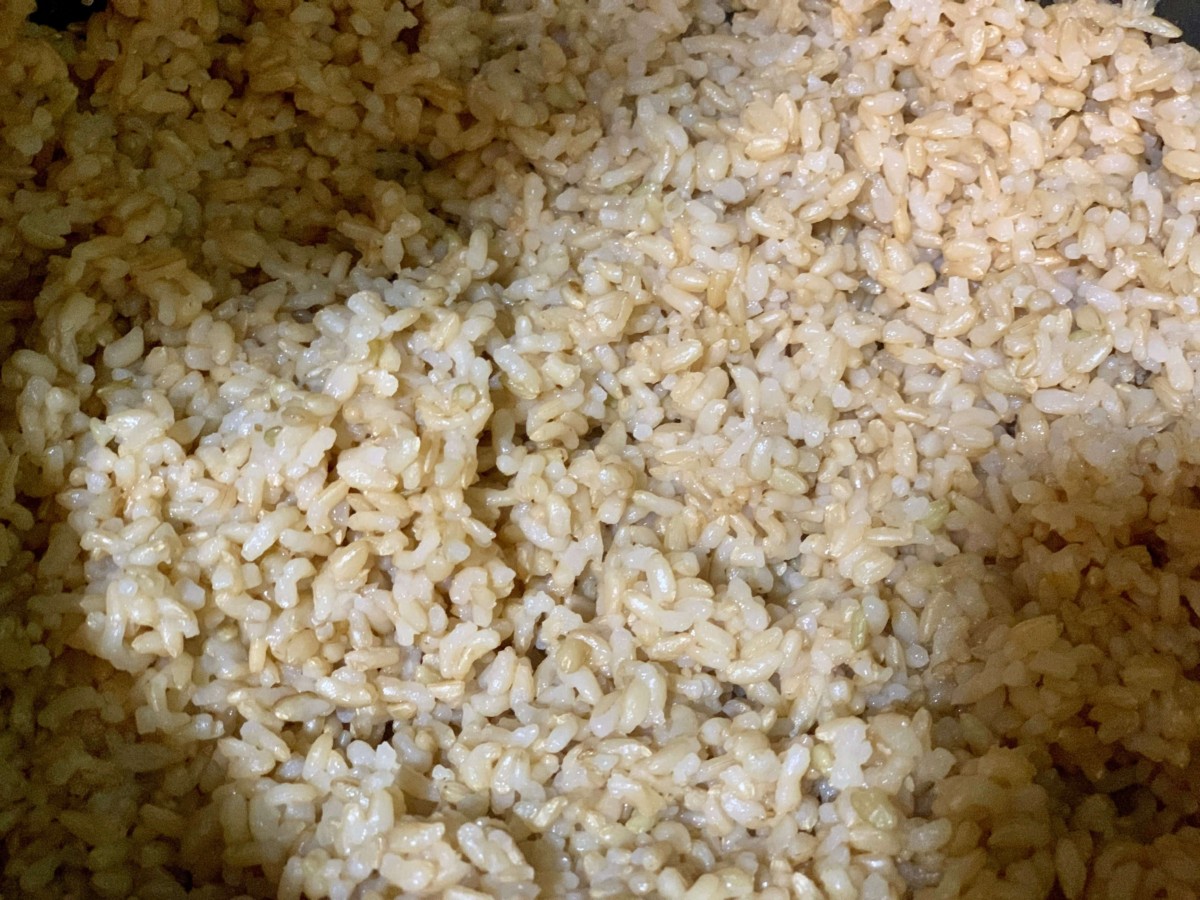

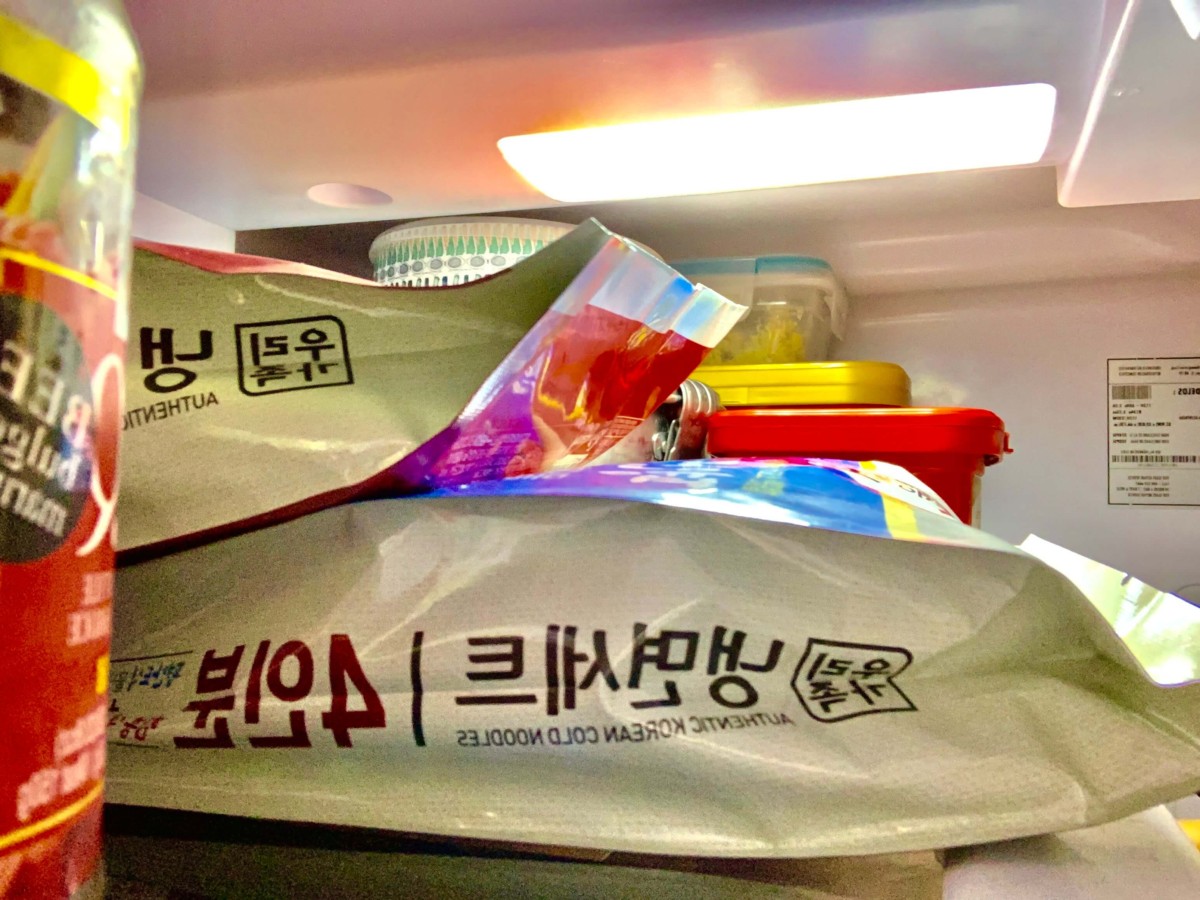

Because I go home, and eat my mom’s miyeokguk. An ugly seaweed monster of a meal that Americans might wrestle with their fork, killing it dead. As I sit and savor the taste before I swallow, dinnertime extends to hours, hours where I can heal with my family. In the New York Times’ “Keeping Love Close” photo collection, a response by Asian-American photographers on what love looks like in a time of hate, the most common theme was food. Fathers divvying up seaweed pancakes amongst mismatched plates. Mothers dressed in outdated patterns, using chopsticks to guide steamed eggs into their children’s mouths. Many were just images of plates of food, vibrantly and proudly strange. So, case in point, food is love.

I’ve written this piece and curated these images to serve as a reminder: the ignored and villainized, we have ways to heal. For much of the AAPI community, it’s food, it’s flavor, and it’s beautifully misshapen. May is over, but food is eternally ours and that’s what makes it sacred.